The Palace of Knossos is one of those rare archaeological sites where myth, legend and excavated stone fuse into a vivid sense of place. Set among low hills just south of Heraklion on Crete, it was the ceremonial and political center of Minoan civilization and is often called Europe’s oldest city.

Today, carefully restored walls and vivid fresco replicas guide visitors through a labyrinthine complex that evokes King Minos, the Minotaur and the story of Theseus, while also revealing a sophisticated Bronze Age society. This guide brings together the latest practical information with historical context so you can understand the site’s layout, plan your visit and know exactly what to expect when you walk into the heart of ancient Minoan Crete.

A Brief History of Knossos and the Minoans

The Palace of Knossos stands on Kephala Hill, about 5 kilometers southeast of modern Heraklion. Archaeological evidence suggests that the first significant settlement here dates to the Neolithic period, around 7000 BC, but Knossos truly flourished during the Bronze Age, when the Minoans dominated the Aegean. The first palace complex is usually dated to around 1900 BC. This original palace suffered earthquake damage and was rebuilt and enlarged in stages, creating the sprawling, multi-level layout visitors see partly reconstructed today.

Minoan civilization, centered on Crete, was notable for its maritime power, refined art, well-planned architecture and advanced infrastructure. At Knossos, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of complex water management, paved courts, painted plaster walls and extensive storage facilities. These features indicate an elite administrative and religious hub rather than just a royal residence. The palace controlled agricultural produce collected from the surrounding region and redistributed under a centralized bureaucracy, and it also seems to have played a key ritual role for the island.

Disasters, probably earthquakes combined with fires, repeatedly damaged the palace, and it finally fell into irreversible decline around 1375 BC. By that time, Mycenaean influence from mainland Greece had increased, and Linear B inscriptions show that Greek-speaking elites had taken over some administrative functions at Knossos. The site was never fully reoccupied at its former scale, and over time its ruins were buried, surviving mainly in Greek memory through myths of labyrinths, monstrous creatures and heroic quests.

Systematic excavations began in 1900 under British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who purchased much of the site and carried out extensive digs. He identified the complex as the seat of a powerful Minoan ruler and sharply distinguished this culture from later Mycenaean Greece. Evans also undertook controversial reconstructions using reinforced concrete and vivid fresco reproductions. These reconstructions, now themselves historic, shape how visitors experience Knossos today, blending archaeological evidence with early 20th-century interpretations.

Understanding the Layout: A Labyrinth in Stone

The palace complex at Knossos covers around 20,000 square meters and spreads across multiple levels around a large central courtyard. When you walk through the ruins, it can feel truly labyrinthine, and this sense of complexity is one reason later Greeks linked the site to the mythic Labyrinth that housed the Minotaur. Rather than a maze designed to confuse, however, Knossos is a carefully organized structure that reflects Minoan priorities: ritual, administration, storage and elite residential life.

At its heart is the central court, an elongated open space used for processions, ceremonies and perhaps performance events. On its west side lie the main ceremonial and religious spaces, including storerooms, shrines and the famous Throne Room. The eastern side contains the grand staircase and a series of residential quarters and light wells that would have brought natural illumination deep into the palace. The north and south entrances link the complex to roads and to the wider Minoan landscape of villas, smaller settlements and harbor installations.

Visitors today generally follow a roughly circular route that begins near the west entrance, moves toward the central court, then loops through key features such as the Throne Room, the grand staircase, the royal apartments and restored colonnaded walkways. Raised paths and wooden walkways guide foot traffic to protect the site, so the route is mostly fixed, though you can pause where space allows. It is helpful to pick up the site plan at the entrance or use an audio guide, as signage is relatively concise, and the multi-level nature of the remains can be confusing without a map.

Beyond the main palace, the broader archaeological zone includes surrounding houses, workshops and cemeteries, though only selected areas are visible to the public. The relationship between the palace and these satellite structures reinforces Knossos’s role as a central node in a networked landscape, with roads leading toward ports and rural areas that supplied the palace with goods and labor.

Key Areas and Highlights Inside the Palace

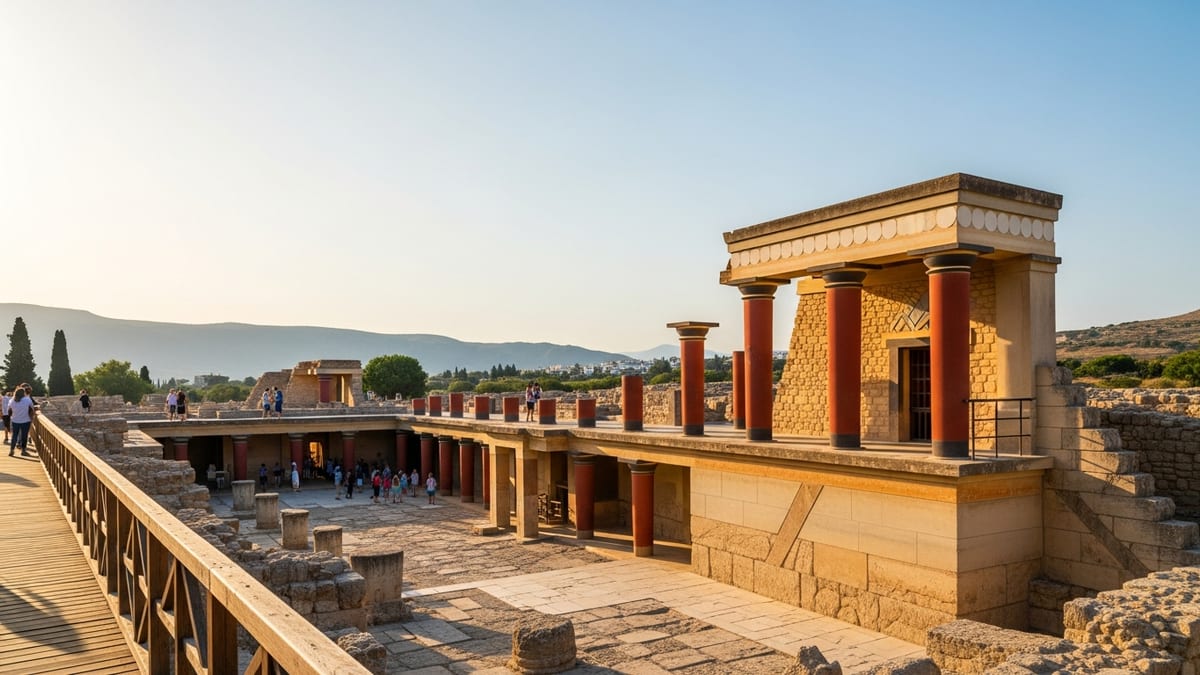

Most visitors come to Knossos with a handful of iconic images in mind: the red columns, vivid bull-leaping scenes and the mysterious gypsum throne. These elements are concentrated in a few key areas, which you should prioritize if time is short. The central court is usually one of the first dramatic spaces you encounter. Its scale and orientation anchor the whole complex. From here, look to the south and north for reconstructed porticoes and stairways that convey the original multi-story effect of the palace.

The Throne Room is one of Knossos’s most atmospheric spaces. Access is often controlled, with visitors peering into the compact chamber from a roped-off area. Inside is a carved gypsum seat set against a wall decorated with replicas of griffin frescoes. A lustral basin, possibly used for ritual purification, sits nearby. Scholars still debate whether the throne belonged to a king, a priestess or served a symbolic function, but the room clearly had ceremonial importance in the later phases of the palace.

On the eastern side, the grand staircase and associated residential quarters reveal the sophistication of Minoan architecture. The stairs once led to upper stories, now vanished, but the surviving levels and supporting pillars suggest airy, terrace-like rooms linked by light wells and corridors. Here you get a sense of how vertical the palace actually was, with multiple floors stacked above storerooms and service spaces. Even in ruin, it evokes a complex, almost urban environment.

Other highlights include the so-called Queen’s Megaron, with its dolphin fresco replica and nearby bathroom area, which hints at advanced drainage and bathing facilities. Storage magazines lined with large clay pithoi jars demonstrate the palace’s economic function, holding oil, grain and other commodities. Around the edges of the complex, restored facades and painted reconstructions, such as the famous charging bull fresco group, bring Minoan visual culture to life. Many of the original masterpieces, however, are preserved in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, so pairing a palace visit with time at the museum completes the picture.

Practical Information: Hours, Tickets and Best Time to Visit

The Palace of Knossos is open year-round, with extended hours in summer to match the long daylight. Recent schedules indicate that from roughly April 1 to August 31 the site usually opens at 8:00 in the morning and remains open until around 19:00 to 20:00 on most days, while from November 1 to March 31 it typically operates from 8:00 to 17:00, with last admission about 15 minutes before closing. In shoulder months such as September and October, closing time gradually shifts earlier in the evening, often around 18:00 to 19:00 depending on the exact date.

The palace is generally closed on major Greek public holidays, including January 1, March 25, May 1, Easter Sunday (Orthodox calendar), and December 25 and 26. On certain special days, such as European Heritage Days or the first Sunday of the month in the November to March period, entry is sometimes free. However, details can change, so it is sensible to check the latest official schedule shortly before your visit and to be aware of any one-off closures or reduced hours associated with national events.

Ticket prices can vary slightly by season and policy updates, but recent information suggests that a standard adult ticket to Knossos alone is in the mid-teens in euros. There is usually a combined ticket that covers both the Palace of Knossos and the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, valid for multiple days with one entry per site, at a modest premium over the palace-only ticket. Reduced admission is typically offered to European Union seniors over 65 and to certain student categories, with free entry for children and young people under a specified age and for EU students. Eligibility requires presenting an ID or student card at the ticket booth.

The site is extremely popular, attracting around a million visitors per year, which means queues for on-the-spot tickets can be substantial at busy times. Many travelers now opt for advance e-tickets through the Greek Ministry’s official portal or authorized partners to avoid long waits. Standard visits take around 1.5 to 2 hours if you focus on the main highlights, but history enthusiasts often spend 3 to 4 hours exploring in detail, especially when using a guide or audio tour.

Planning Your Visit: When to Go and How to Get There

Choosing the right time of year and day can significantly improve your experience at Knossos. Crete’s high season runs from about June through early September, and July and August in particular can bring mid-day temperatures over 30 degrees Celsius, alongside tour bus crowds. In these months, visiting right at opening time around 8:00, or in the final two hours before closing, helps you avoid both peak heat and the most intense congestion. Mid-day, roughly between 10:00 and 16:00, is usually the busiest period, especially when cruise ship excursions converge on the site.

Spring and autumn, roughly April to early June and September to October, are widely regarded as the most pleasant seasons for Knossos. Temperatures are generally milder, the light is softer and the crowds slightly more manageable, although it remains a popular attraction. Winter visits, from November through March, bring the smallest visitor numbers and comfortable walking weather, but you should be prepared for shorter daylight, occasional rain and reduced hours or services. Weekdays are generally calmer than weekends, and Tuesday through Thursday often feel quieter than Monday or Friday, when new arrivals and weekend travelers are more likely.

Getting to Knossos from Heraklion is straightforward. The site lies approximately 5 kilometers south of the city center along the main Knossos Avenue. By public transport, local bus line 2 runs regularly from Heraklion’s central bus area to the palace, with Knossos as the final stop; the ride usually takes about 15 to 20 minutes. Taxis from the city center or from Heraklion’s port and airport are easy to arrange and typically take 10 to 15 minutes, depending on traffic. For those with a rental car, the drive is simple, and there is a car park adjacent to the main entrance, though it can fill up by late morning in high season.

If you are arriving on a day trip from elsewhere on Crete, organized excursions are widely available from resort towns such as Chania, Rethymno and Agios Nikolaos. These often combine a guided palace visit with time in Heraklion and at the archaeological museum. For independent travelers, renting a car provides flexibility to time your visit to early morning or late afternoon and to combine Knossos with other nearby sites or coastal stops.

Guided Tours, Accessibility and On-Site Facilities

Given the complexity of the ruins and the layered interpretations of Minoan culture, many travelers find that a guided tour dramatically enhances their visit. Licensed guides are often available near the entrance for ad hoc small-group or private tours, and numerous agencies offer pre-booked guided visits that include transport from Heraklion or other towns. A good guide can weave together archaeology, myth and modern scholarship, explaining debates such as how much of what you see is reconstruction and how gender, religion and power may have operated in Minoan society.

For independent visitors, audio guides and digital companions are increasingly common. Several ticket options now bundle entry with a smartphone-based audio tour or app that uses GPS or numbered stops to orient you at the site. These resources typically include maps, background essays and thematic commentary, and they are valuable if you prefer to move at your own pace but still want substantive interpretation. Even with an audio guide, it is helpful to glance at the site plan boards to keep your bearings in the multi-level layout.

In terms of accessibility, Knossos occupies a low hill with a mix of paved walkways, gravel paths and original stone surfaces. Some sections have ramps and relatively level routes that can be navigated with wheelchairs or strollers, especially around the central court and main viewpoints. However, other areas involve steps, uneven stones and narrow passages. Visitors with mobility challenges should be prepared that not all parts of the palace will be accessible, though much can still be seen from exterior viewpoints and designated routes. It is advisable to wear sturdy footwear with good grip, as polished stone and loose gravel can be slippery.

Basic facilities at the site include ticket booths, restrooms and small kiosks near the entrance selling water, soft drinks and light refreshments. There is usually a gift shop with books, replicas and souvenirs related to Minoan art and archaeology. Shade can be limited within the ruins themselves, particularly in the central court and upper walkways, so bringing a hat, sunscreen and sufficient water is essential in warm weather. Benches are scattered in some shaded corners, offering welcome rest spots while you absorb the atmosphere.

Making Sense of the Reconstructions and the Myths

One of the most distinctive aspects of visiting Knossos is the presence of reconstructed buildings and frescoes. Unlike many Greek archaeological sites where only foundations remain, here you will see concrete pillars, painted columns and partially rebuilt rooms. These are largely the result of Sir Arthur Evans’s early 20th-century efforts to give visitors a clearer sense of the palace’s original appearance. While his work was pioneering for its time, modern archaeologists sometimes criticize the reconstructions as imaginative or overly interpretive.

As you explore, it is helpful to remember that some elements reflect Evans’s vision of a peaceful, matriarchal Minoan society, which current scholarship often views as overly romanticized. For instance, the emphasis on female figures and priestesses in fresco reconstructions and interpretations of rooms like the Queen’s Megaron may reflect as much of his cultural context as of Bronze Age reality. Today, archaeologists stress that Minoan society was likely more complex, with power structures that we still do not fully understand. Treat reconstructed frescoes as evocative visualizations rather than literal windows into the past.

The myths associated with Knossos continue to exert a powerful pull. According to Greek tradition, King Minos commissioned the architect Daedalus to build a labyrinth beneath his palace to contain the Minotaur, a creature half-man, half-bull born from divine entanglements. The hero Theseus eventually slew the beast with the help of Minos’s daughter Ariadne, who supplied a ball of thread to guide his escape. When you walk through the multi-level corridors and rooms of Knossos, it is easy to see how such tales could emerge from folk memories of a vast palace complex long after its original purpose was forgotten.

Modern guides often use these myths as storytelling tools to engage visitors, especially families with children, illustrating how archaeology and legend intersect. Yet the real story of Knossos is at least as intriguing: a sophisticated society with far-reaching trade networks, an undeciphered script known as Linear A and an artistic style that combined naturalism with stylized elegance. Allow time at the site simply to absorb the details of stonework, column placement and light wells, as they hint at everyday experiences of ancient inhabitants that no myth fully captures.

The Takeaway

A visit to the Palace of Knossos is far more than a tick-box stop on a Greek island itinerary. It is an encounter with one of the earliest complex societies in Europe, framed by stories that have shaped Western imagination for millennia. Walking through its courts and corridors, you are seeing both the tangible remains of Minoan architecture and a century of archaeological interpretation layered on top. To appreciate Knossos fully, it helps to balance wonder with critical curiosity, admiring the reconstructions while remembering their speculative elements.

From a practical standpoint, timing your visit for early morning or late afternoon, securing advance tickets and pairing the palace with the Heraklion Archaeological Museum will yield the richest experience. On-site, move slowly, study the site plan and let key spaces such as the central court, Throne Room and grand staircase sink in. Whether you come as a dedicated history enthusiast or a curious island traveler, Knossos rewards attention with a compelling blend of stone, story and sea-breeze light that lingers long after you leave the hilltop and return to modern Crete.

FAQ

Q1. Where is the Palace of Knossos located?

The Palace of Knossos is situated on Kephala Hill about 5 kilometers southeast of the city center of Heraklion on the island of Crete in Greece.

Q2. How long should I plan for a visit to Knossos?

Most visitors spend around 1.5 to 2 hours exploring the main highlights, but history enthusiasts or those using a guide or audio tour often allow 3 to 4 hours to see the site in more depth.

Q3. What are the typical opening hours of the palace?

In recent years the site has usually opened daily at 8:00, with closing times around 19:00 to 20:00 in summer and about 17:00 in winter, with last admission roughly 15 minutes before closing, though exact times can vary by season and date.

Q4. Do I need to buy tickets in advance?

You can buy tickets at the entrance, but in high season queues can be long, so many visitors prefer to purchase advance e-tickets through official or authorized channels to reduce waiting time.

Q5. Is there a combined ticket for Knossos and the Heraklion Archaeological Museum?

Yes, there is typically a combined ticket option that covers one visit to the Palace of Knossos and one visit to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum within a set number of days, offering convenience and good value.

Q6. How do I get to Knossos from Heraklion without a car?

You can take local bus line 2 from central Heraklion, which runs frequently and terminates at the Knossos stop near the entrance, or use a taxi, which usually takes around 10 to 15 minutes from the city center or port.

Q7. Is Knossos suitable for visitors with limited mobility?

Some areas of the site are accessible via ramps and relatively even paths, but other sections involve steps and uneven surfaces, so not all of the palace is easily reachable for wheelchair users or those with significant mobility challenges.

Q8. What should I wear and bring when visiting?

Comfortable, closed-toe walking shoes, a hat, sunscreen and sufficient water are strongly recommended, as paths can be uneven and shade is limited, especially during the warmer months.

Q9. Are guided tours worth it at Knossos?

Many visitors find guided tours highly worthwhile, as licensed guides and structured audio tours provide context on Minoan history, architecture and mythology that can be difficult to grasp from signage alone.

Q10. Can I see the original frescoes and artifacts from Knossos on-site?

Most of the most important frescoes and portable artifacts from Knossos are housed in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, while the palace displays high-quality replicas and architectural remains in their original setting.